Weed, obviously. But also a ton of innovation, some surprising ingredients, a dose of hucksterism—and a tradition on the verge of being extinguished.

"So ,” I ask Seth Rogen, “how many joints do you roll a week?”

“I don’t know. Between fifty and seventy-five.”

“Can you roll while we talk?”

Stupid question. Anyone who rolls fifty-plus joints a week can roll while he talks. But Rogen lets it slide.

“Sure. I can roll. Let me try to find a surface.”

And with that, Rogen, he of stoner-film fame, locates a surface and begins rolling while we’re talking, his fingers dancing across the paper as he preps, stuffs, shapes, and twists. Rogen is in Los Angeles, taking a break from working on The Studio, a new TV show he’s writing, directing, and acting in, while I’m in New Mexico, taking a break from eating Fritos. While Rogen rolls, I reach for the joint I’d spent eleven minutes readying the night before, as I did not want to bring shame upon my head by trying to sculpt a jay in front of one of the five most celebrated puffers on earth. Out of Zoom’s view, I primp my wilting doobie one final time before casually revealing it to the camera. Rogen doesn’t notice.

“What are you putting inside?” I ask.

“Sativa. A Jack Herer variety.”

“And what are you rolling with?”

“Brown rice paper.”

At which point, precisely forty-one seconds after he began, Rogen completes his task. Like a man who’s caught a beautiful, perfectly proportioned if very small bass, he holds it up to the camera.

The joint is flawless.

“There you go. I roll the tube and then I’ll seal one end, then I roll up the filter and I use that to kind of like, you know, pack the joint.” Rogen flicks a flame to his brown torpedo. I do the same to mine. We are now in a smoke-filled Zoom.

“Fifty to seventy-five joints a week,” I say. “What is it about the physical act of rolling that you like?”

“Nothing. The truth is,” he says, growing animated and ticking off the whys on his fingers, “there’s not a pre-roll that exists that has the type of weed I want in it, rolled the way I want. It’s mostly that I just like to smoke joints and I like a very specific type of weed, and the marriage of those two. I like to smoke a specific type of joint. I don’t like cones. I like my joints to be very, like, cylindrical. I don’t like them to be too big. I don’t want them unwieldy. I want them to have a filter. I have, like, a pretty specific thing I’m going for. And so I have to do it myself in order to get what I’m actually looking for.”

“Why not hit a bong or a pipe?”

“It’s just not the same. I actually think I get, like, a different type of high from smoking a joint versus a pipe or a bong. And that’s the feeling that I am personally looking for.”

And this is the reason I’m speaking with Rogen. Yes, of course, he starred in cannabis-infused classics like Pineapple Express and Knocked Up, but Rogen makes more than movies. He makes earthy ceramic ashtrays, stylish pour-over sets, and crackled-clay candleholders for his design-forward side hustle, a weed-adjacent, deeply domestic lifestyle brand called Houseplant. And recently he launched his own line of, yes, rolling papers. Not industrial-chic vapes or Bauhaus-inspired bongs but good old-fashioned, coupla-bucks-a-pack rolling papers.

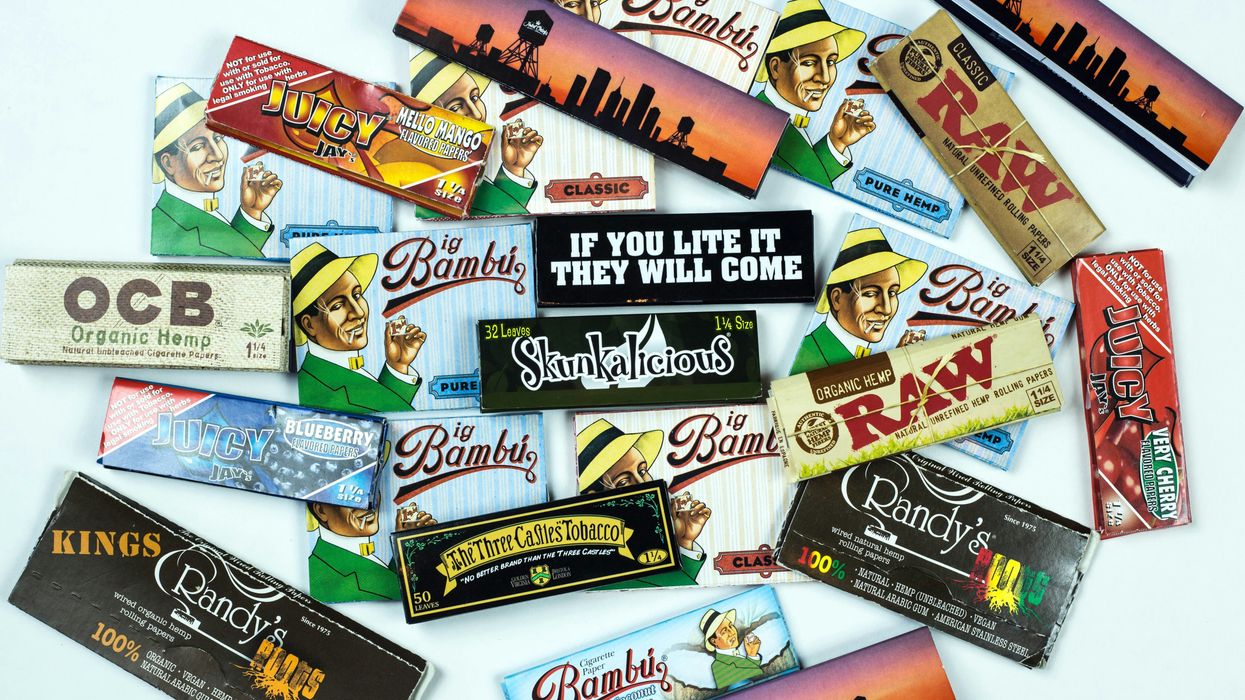

Rogen tells me that he and his Houseplant team spent years thinking about and researching papers. Not surprisingly, he was looking for a well-constructed, clean paper but also one produced by a company that put a premium on both transparency and environmental sustainability. He landed on OCB, a century-old company now owned by Republic Brands. Rogen and Houseplant decided to carry OCB’s brown rice, classic white, and bamboo papers and then went about designing packaging for the Houseplant-branded booklets. His biodegradable booklets are classy—clean lines, sophisticated typeface, unexpected colors. “They aren’t designed to blend in with your coffee table,” he says. “They’re designed to be a centerpiece, and that truly does destigmatize the whole act of weed smoking.”

Rolling Papers Unpacked

WHEN I STARTED ROLLING JOINTS, back in my early teens—back in the late seventies—getting high was stigmatized, but it was also pretty straightforward. Gummies, vapes, tinctures, topicals, dabs, shatter, oral sprays, THC-lined drinking straws, THC-saturated coffee pods, and cannabis-infused sparkling beverage products didn’t exist. Bongs were too big to be reliably hidden from our parents; the bulge that a pipe made in the front pocket of our Levi’s was awkward, unseemly. So we turned to rolling papers, which could be surreptitiously slipped into a sock drawer or pocket, which were affordable on a five-dollar-a-week allowance, and which, with a bit of practice using a few pinches of Mom’s oregano, allowed us to exhibit a modicum of mastery in a world we were still trying to figure out.

In those days, I carried a booklet of Zig-Zags everywhere, for reasons both totemistic and pragmatic. When our attempt at crafting a Mountain Dew–bottle gravity bong failed, we reached for our papers. When our pipe got confiscated on the way into the Stones concert, we reached for our papers. But the moment I realized that rolling papers had qualities beyond the purely practical—the moment I realized they had a certain romance to them—came in my early twenties: I was in a café in Paris with a dark-eyed American woman I’d just met. We were drinking wine and she began rolling a cigarette. She rolled with cred and confidence, never once breaking eye contact to look at her handiwork. When she slowly ran her tongue across the paper, my heart skipped a beat. Twenty years later, we got divorced.

During the kid-raising years, when I’d sworn off smoke, I’d catch myself looking with gauzy nostalgia at the rolling papers displayed behind convenience-store counters—Bambú and Bugler, Rizla and Raw, E-Z Wider and, of course, Zig-Zags. And then, as legalization gathered momentum, THC-delivery methods became both increasingly diversified and alluring: Edibles made getting high absurdly easy, vapes took a load off your lungs, goofy-ass bongs got an Alessi-like makeover, even dabbing no longer required a torch-driven kit that screamed “Meth!” In what can only be described as the domestication of what we once called “dope,” technical innovations suddenly made it possible for you to sip your smoke from a wine-like glass and prepare multi-course meals with infused ingredients.

And rolling papers? Well, they still lived in little cardboard booklets just as they always had—but dispensaries seemed to be elbowing them off the shelves to make room for trendier products. For new users, of which there were now many, sucking on a cute, watermelon-margarita-flavored gummy was clearly less intimidating than teaching themselves how to roll a proper joint. In fact, at this point in the evolution of cannabis culture, it’s fair to ask a question that once would have been considered laughable or heretical or both: Will rolling papers—the exoskeletal signifier of the counterculture, the symbol of mind expansion, of freedom, of peace and love, of the munchies—face extinction at the hands of the very subculture they sparked?

My own hands? Maybe not so clean. As I looked at my stash of edibles, at my shelf of whiz-bang smoking contraptions, I had to admit that for nearly five decades, I’d taken the humble rolling paper pretty much for granted. For the hundreds of papers I’d purchased, carried, filled, rolled, and lit, I realized I knew next to nothing about them. And so, fearing the sacred emblems of my youth were destined for history’s ashtray, I set out to unpack the rolling paper. In the end, I would travel thousands of miles to visit the site where most of the world’s papers are made, would meet the Henry Ford of rolling papers, would hear from data analysts and OG rollers about what we’d lose if this whisper-thin piece of paper that’s shaped our culture for so long actually were to become obsolete.

Anatomy of a Rolling Paper

ALTHOUGH ROGEN TALKS ABOUT DESTIGMATIZATION, it’s not what led the seemingly carefree chucklehead stoner deep into the nitty-gritty science of the rolling-paper industry. “In Canada, we were making pre-roll joints, and the Canadian government told us that the papers we were using were not up to their health standards,” he says. “Which indicated that they might not be made out of what they said they were made out of. . . . Honestly, that was the first thing that scared the shit out of me.”

At which point he breaks into his trademark yuk-yuk-yuk and adds: “I smoke so many joints, and I’m getting older, and I really wanted to know that I was using the best possible paper to smoke my joints.”

But because rolling papers are barely regulated and aren’t required to list their ingredients—and in the U.S. aren’t even tested in every state—it’s nearly impossible to know what’s in the paper you’re inhaling. There can be additives that change the color of the ash, alter the burn speed, brighten the white of the paper. You know those pre-rolls with the company logos on them, and those papers that come in spanky colors? A recent academic study detected eyebrow-raising levels of heavy metals—including copper, chromium, and vanadium—in many of these papers, due in large part to the ink and artificial dyes. (As one rolling-paper CEO told me, “If you’re adding ink to paper, it’s going to have heavy metals. It’s not a question mark. It’s how much.”) Flavored papers can also be problematic, as the “flavor” is often a sprayed-on artificial coating.

Likewise, while some papers promote themselves as being “organic,” “vegan,” or “gluten-free”—sounding more like an Erewhon muffin than a tube for Durban Poison—you can’t really know which marketing claims are mere puffery. In 2023, a federal court ordered Raw, the rolling-paper powerhouse, to stop making certain claims on its packaging, including that its organic hemp papers are “unrefined,” made from “the center of the stalk,” or made from “natural hemp gum.” Forbes magazine characterized the company at the time as “relying on deceitful claims and aggressive hucksterism.”

There are also promises made on booklet labels that, while not deceptive, are hard to parse: There’s no industry-standard definition for what terms like “thin” and “slow burning” actually mean. On the flip side, not all papers that are whitened or “bleached” necessarily use chlorine or other chemicals; OCB papers, for instance, are whitened with an oxygenation process that leaves no residue.

That said, the material your paper is made from can steer your selection. In one lab I visited, I looked at papers under a microscope and could see the plant fibers from which they were made. Turns out it’s the fibers that drive the smoking experience.

Wood-pulp fibers, from which most rolling papers are still made, are long and tightly packed, which leads to a faster burn rate—and a shorter smoking session. Wood-based papers’ relative thickness provides more structure, allowing joints to hold their shape better than those using papers made from other materials, a trait appreciated by beginning rollers. However, that thickness also increases the burn speed and can overwhelm the natural flavors of the cannabis. Back in the day, when weed tasted like hot dirt and taking quick hits behind a 7-Eleven was the norm, this was acceptable. But legalization means there’s no need to rush, so when your Lemon Haze actually tastes like fresh-picked citrus, it makes sense to take a beat and enjoy what the plant has to offer.

Papers made from hemp are thinner than those made from wood, offering a slower burn, a smoother smoke, and a slight earthy taste. The differences between papers can be subtle, and much of it comes down to personal preference, but environmentally conscious smokers are increasingly turning to hemp, a sustainable crop that grows quickly, requires minimal chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and uses far less water. Growing a single tree takes years; papers made from hemp or rice go from seed to store in a single year.

Producing rolling paper from rice, with its short fibers, is notoriously difficult—so difficult, in fact, that some of the so-called “rice papers” on the market are not actually made entirely from, you know, rice. Republic, the company that manufactures the OCB brand Rogen selected, spent three years developing a blend of rice and hemp—as well as the technology to position the fibers in a specific way—to create an incredibly thin paper that’s strong enough to stand up to fingers and flame. Rice paper’s thinness can make it harder for new rollers to handle, and rice joints tend to need relighting, but the payoff comes in a clean smoke that doesn’t bigfoot the plant’s flavor, a silky-to-the-touch feel, a slow and even burn, less ash, eco-friendliness, and something Rogen gets excited about: “You can actually see, like, the rice grains in the paper!”

How Legalization Changed Smoking

THE SHEER TONNAGE OF GOOD HERB that “recreational use” unleashed on the market is reshaping the way America gets high—and the way we roll. One smoking tradition has pretty much vanished: pinching the microscopic end of the joint—the roach—as your fingers blackened and burned. Roach clips, which were often adorned with a feather and dangled moronically from rearview mirrors, have also been benched. My kids, twenty-five and twenty-two, have used a roach clip exactly as often as they’ve used a typewriter. Auryn McCafferty, an award-winning breeder and the founder of Purple City Genetics in Oakland, told me that the last time he visited his father, a seventy-five-year-old OG smoker and onetime black-market weed “entrepreneur,” he watched, stupefied, as his old man pulled an itsy-bitsy roach from the ashtray, clipped it, lit it, and hit it. “I was like, ‘What the fuck are you doing? There’s plenty of weed around! There are dispensaries everywhere! You look crazy doing that!’”

Likewise, the “fatty,” once the Holy Grail for every pothead I ever knew, is being kicked to the curb by the “dogwalker,” a half-pint joint not meant to get you walleyed stoned but rather tailored to take the edge off your twenty-minute poop-scooping stroll. (As one friend put it, “Weed is so strong now that not many of us require the services of a spliff as fat as your finger.”) I’m seeing guests bring a box of dogwalkers to parties in lieu of a bottle of Bordeaux.

But the biggest shift—and the biggest boost—to the nearly $1 billion rolling-paper market is the wildfire spread of the pre-roll, along with its slightly more DIY cousin, the empty cone. Both the pre-roll (which comes loaded and lighter ready) and the cone (a perfectly shaped but empty vessel in which the smoker stuffs his choice of herb) are beyond convenient, always look spectacular, and continue to grow in popularity. According to Mitchell Laferla, an analyst at Headset, a top cannabis data-analytics firm, pre-rolls are now the number-three category among consumers (behind flower and vapes), taking a 15.3 percent slice of the market. Women in particular are leaning into pre-rolls: Women purchase 35 percent of all cannabis categories but are responsible for a comparatively higher share—39 percent—of pre-roll sales, a number that has only increased over the past few years.

The knock on pre-rolls was always that they were a cylindrical home for old, unwanted, possibly moldy shake and trim that, shrouded by the rolling paper, a user would never see. (“They had a stigma. I wouldn’t touch ’em,” says McCafferty.) But pre-rolls have gotten a glow-up thanks to the recent trend of infusing them with a high-potency concentrate like wax or hash. Sales stats for rolling papers meant for cannabis use are impossible to untangle from those intended for tobacco (most papers are still sold at convenience stores and gas stations, and there’s no telling what a purchase is intended for), but Laferla says that for the first eight months of 2024, pre-roll sales easily cleared $2 billion.

The Perils of Perfection

WHERE DO ALL THESE PRE-ROLLS COME FROM? Let’s start with the paper casing. Odds are the paper for the next pre-roll or empty cone you buy was assembled by hand and in about fifteen seconds by one of the four thousand mostly female employees of Hara Supply, the King Kong of the cone world. Hara, founded in 2017 by two guys who’d once been roommates at George Washington University, now has nine massive factories in and around Delhi, India, dedicated to cone making. Last year, Hara produced well over a billion cones.

When I ask Bryan Gerber, Hara’s thirty-three-year-old cofounder and CEO, about the factors driving our country’s pre-roll love, he says, “They’re obviously convenient, but it’s also about physics.” Physics? “The draw of the airflow, from a larger point to a skinnier point, is the way that cannabis should be smoked,” he explains. “When you roll your own, it doesn’t typically burn evenly and you often get too much airflow coming through, which is why you cough. A cone channels the smoke into this tighter window, into the filter tip, cooling it as that’s happening.”

Once constructed, Hara’s cones are shipped to dispensaries and vertically integrated cannabis companies in the States, which will fill them with their own strains. The machines that do this are kind of a trip: Imagine a flat colander topped with ground-up weed that shimmies and vibrates as the flower sifts into dozens of waiting, open-mouthed cones. Most machines can adjust the weight of each batch of pre-rolls as well as how tightly they’re packed. One high-end “knockbox,” the dishwasher-sized STM RocketBox 2.0, costs a mere $18,570 and promises a 453-joints-in-five-minutes fill rate; it even provides an automatic, fancy-pants “Dutch Crown” fold at the end, rendering the Platonically perfect joint.

But perfection is a funny thing, one that can rub up uncomfortably against the loosey-goosey weed ethos that predates the current cannabis-as-packaged-goods era. With the onset of antiseptic Apple Store chic—visible in dispensaries, product packaging, and, yes, the pre-roll—comes a disconnect from the plant itself, meaning that a pre-roll smoker no longer needs to touch or even see the source of his high.

Pre-rolls most definitely giveth in terms of aesthetics and consistency, but they also taketh away. The inveterate weedsters I spoke with about old-fashioned rolling lamented the loss of “foreplay, you know, the anticipation,” “a James Bond–like expertise,” “a link to the past,” “control over what you ingest,” and “Dude, there’s nothing social about a pre-roll.” In fact, in the short ten years since the country’s first recreational dispensary opened, it’s become harder and harder to find a twenty-something who can roll. Or who even wants to roll. “Rolling is becoming a lost art,” Gerber says.

Not every longtime roller believes that’s so bad. Verena von Pfetten, cofounder of Gossamer, a gorgeous cannabis-friendly magazine and lifestyle brand, is steeped in both trends and traditions. She told me that in the publication’s early days, circa 2018, she felt that rolling know-how was a must, especially for women, because in a male-dominated industry, “showing that a woman could be as much of a connoisseur of cannabis as a man was important. And part of that had to do with rolling a joint.” The joint-rolling workshops von Pfetten led for women sometimes had as many as sixty students in attendance.

“But as I’ve gotten older and as the industry has grown up,” she says, rolling has become less consequential to cannabis cred. “I can roll a joint if I want to, but I no longer feel the need to prove myself.” Rolling skills still carry social weight, she says, “but the juice isn’t always worth the squeeze.” For one thing, “I don’t even remember the last time I smoked an entire joint. Weed is so strong now that I might take a couple hits, then put it out, then pick it up the next day, then put it out, and at a certain point, even the most beautiful hand-rolled joint isn’t that beautiful anymore.”

Rolling Towards Bethlehem

ONE OF THE FIRST COMPANIES to produce rolling papers also made the thin, strong, beautifully bright pages that filled . . . Bibles. I have that fact in mind as I enter the factory where, some 105 years ago, brothers Jacques and Maurice Braunstein began churning out their revolutionary rolling papers—Zig-Zags—at scale. In 1894, the French frères, name-checked on every booklet of Zig-Zags, figured out that folding (or “interleaving”) the papers in the shape of a Z, with the edge of one paper tucked into the crease of the next, allowed the first paper pulled from the booklet to seamlessly draw the second into position—not unlike a paper-towel dispenser. This upgrade removed just enough friction from the process to turn the brand into a global icon. Today, Zig-Zags account for nearly one of every three booklets sold in the U.S. For old-schoolers like me, this factory can only be described as rolling-paper Bethlehem.

“The first rolling papers I ever heard of were Zig-Zags,” Rogen told me. Same here. And if the teenage me, the kid who looked at Jeff Spicoli and thought “role model,” had known that one day his middle-aged, nearly bald self would amble into the very manger where millions and millions of Zig-Zags were born, I can tell you this: He’d have laughed his ass off.

It was here, on the floor of this factory, that the mysterious Zig-Zag man—bearded, dressed in an open jacket and head wrap, a smoke in one hand and a pack of papers in the other—graced booklet after booklet coming off the line. The Zig-Zag man is modeled after a Zouave, a soldier in an elite North African unit that fought for the French in the Crimean War. According to a chronologically dubious and likely apocryphal legend, during the violent Battle of Sevastopol, a bullet pierced a Zouave’s pipe and, desperate for a smoke, he MacGyvered a hand-rolled cigarette using paper he tore from his bag of gunpowder. Improbably, the Zouave has come to stand not just for a few moments of smoky pleasure and not just for a brand but for counterculture itself.

The old Braunstein factory sits a thousand yards from the effete Evian bottling plant in a smallish French town called Thonon-les-Bains, on the green lip of Lake Geneva—papermaking requires a merde-load of water—with the Alps beginning their steep climb just behind it. Today the plant produces all the paper used in Zig-Zags but also in OCB, JOB, E-Z Wider, Top, Joker, Abadie Paris, and the other brands owned by Republic.

I was expecting something weed-y and Willy Wonka–esque, but the factory looks like the set for a World War II–era village on a Hollywood back lot, a collection of hardworking, century-old buildings with fading brick chimneys and paint-chipped shutters. This is rolling paper’s working-class roots, where muscle-y Frenchmen with close-cropped hair and protective eyewear move steadily between the buildings. Many of them have parents, possibly grandparents, who worked at the factory before them.

The Man Behind Your Papers

I’M WALKING THE FACTORY GROUNDS with the man who knows more about rolling papers than anyone living or dead. That man is Don Levin, and Don Levin does not look the part. Now in his early seventies, Levin presents as a graying Linus Van Pelt who left Snoopy and blanket behind and began reading The Wall Street Journal. His quick rejoinders land with the nasal, flat a of a Chicago native; his eyes can flick from twinkly to piercingly serious. Levin owns Republic Brands, and for an exceedingly wealthy man, he is exceedingly down-to-earth and can be disarmingly straightforward. (“There’s no good that comes from smoking anything,” he tells me within minutes of our first meeting. “Nothing good is happening to your lungs, right?”) If you’ve ever rolled a joint, there’s an extremely good chance you’ve set a small piece of Don Levin’s life’s work on fire.

In the early seventies, Levin sold his stake in a hippie headshop, Adam’s Apple (“A Progressive General Store”), on the North Side of Chicago and moved into the less-likely-to-be-raided-by-the-cops field of rolling-paper sales. His time at Adam’s Apple had tipped him to the fact that the counterculture was positively desperate for papers (“When I started, people would drive twenty-five miles to find a pack”), and over the past fifty years, he has built what can only be described as a global rolling empire. Taken together, his Republic Brands produce more papers than any other company, an astonishing 1.2 billion booklets a year. Which means that Levin, working quietly, almost invisibly behind the scenes, has arguably done more for pot smokers than mainstream influencers like Seth, Snoop, Woody, or even Willie. One other thing separates Levin from Willie: “I can’t roll,” he says. “I never could. I have no dexterity.”

Levin and I, along with his then chief revenue officer (whose name, I swear on a stack of fresh Bible paper, is Rebecca Roll), enter a huge storage room. Bales of wood, rice, hemp, and flax stacked twenty feet high wait to be soaked, pulped, pressed, dried, turned into paper, and spooled. It feels funny, in a way, that all of these people, all of this raw material, all of this infrastructure—the deep pools of wet glop, the massive conveyor belts and fans, miles of pipes, bobbins the size of cars, a furnace that looks like the entrance to hell itself, not to mention millions of dollars to make the entire process more eco-conscious—live in the service of creating a product whose sole purpose is to be destroyed and leave no trace other than a foggy memory.

Once the raw material is converted into paper, it’s sent a day’s drive south, to Perpignan, an old French coastal city two hours north of Barcelona, where Republic has built the world’s largest, most productive rolling-paper factory. From the outside, it’s straight-up Dunder Mifflin. But inside, a nonstop industrial ballet plays out across 190,000 square feet of factory floor: Massive rolls of paper unspool before me, waiting to be watermarked with a logo then trimmed to rolling size, edged at a rate of hundreds of yards per minute with a thin line of natural Kenyan acacia gum that (once licked) will hold the joint together, and packed into a tight and tidy booklet of thirty-two or so leaves. With Fantasia-like relentlessness, booklet after booklet of Republic’s papers zip down long, humming conveyor belts and land neatly in a branded box bound for one of 104 countries. Everything is temperature regulated, humidity controlled, automated, state-of-the-art; a robot stacks pallets of papers; and there’s even a machine that fixes other machines. If the factory on Lake Geneva was a reminder of rolling paper’s blue-collar past, this feels like its seamless, whirring future.

In the Lab

I’M LED INTO REPUBLIC’S COMPACT, second-floor lab by Santiago “Santi” Sánchez, the company’s president and top engineer. Sánchez, who has logged nearly four decades in the rolling-paper business, is widely considered a paper obsessive, known to scour parking lots frequented by smokers to study their tossed cigarettes for any handmade modifications to the papers, like folded corners, ripped edges, or homespun filters.

In the lab, a few whitecoats conduct quality control on Republic’s rolling papers while also analyzing its competitors’ papers—as well as papers that look like Republic papers but are actually knockoffs. Counterfeits (mainly from China) are an increasing problem in the rolling-paper industry, and when Levin brings up the topic, the twinkle leaves his eyes. “They’re selling dangerous products under my name,” he says, mentioning heavy metals and chemicals, “and that bothers me. That makes me crazy.”

Sánchez points out the microscopes, the machines that measure a paper’s tensile strength, various monitors and scales. The technically challenging goal, of course, is to make a leaf both thin and strong. Regular Zig-Zag papers weigh 14.7 grams per square meter (GSM in industry-speak) compared with, say, a page of my home printer paper, which is closer to 90. At 10 GSM, Republic’s OCB Ultimate is quite possibly the lightest paper on the market. (Allow me to help you win a bar bet: Your average single rolling paper weighs in at .05 grams and withstands about 5.7 pounds of pressure.)

Let the Good Times Roll

GIVEN THAT PEOPLE HAVE BEEN SMOKING in one form or another for thousands of years, and that paper itself has been around since A.D. 105, rolling papers are a surprisingly recent invention. Their origin story is murky: Some accounts have them invented in Spain, others in France. Some in the 1500s, others the 1600s. Was the inventor a soldier, a sailor, a monk? Unclear. But the modern rolling-paper booklet, the thing you and I think of when we think of rolling papers? That was created in France, in 1838, by Jean Bardou, a onetime baker who concluded that carrying around loose sheets of thin paper in one’s pocket was neither user-friendly nor hygienic.

Bardou’s paradigm-shifting innovation was to neatly sandwich his small papers between cardboard and tie up the package with a ribbon. It was the killer app. Right off the bat, business boomed, and he began proudly imprinting the booklets with his initials—JB—slipping a diamond between the letters. Smokers thought the diamond was an O and began calling them “JOB.” Monsieur Bardou embraced his graphic-design flub and before long had himself a recognizable brand and French patent number 8872.

His son Pierre took over the biz in 1853, bought a building in Perpignan, and turned it into a stately mansion and the JOB manufacturing facility. It was a busy spot: At one point, Pierre employed some three hundred women, as well as a suite of steam-powered machines, to assemble the popular booklets. Today, nearly two hundred years after Jean Bardou’s breakthrough, JOB is the number-one-selling paper in the U.S. (Zig-Zag is number two.)

Strolling through the three-story, art nouveau palace that Bardou’s booklets built—through the lush central courtyard, up the interior double-wide staircase, into grand and high-ceilinged salons, past murals of half-naked nymphs frolicking in the sea—I find myself thinking about stick shifts. Once upon a time, the stick shift was the standard. Even as late as 1980, 35 percent of new cars in the U.S. had a stick. Today? Less than 2 percent. What once required style, touch, and timing to operate now requires . . . nothing. And as I thought about the almost inevitable move toward frictionless consumption—mixtapes giving way to automatically generated Spotify playlists, for instance—I pondered the life and possible death of the hand-rolled doobie.

The future of rolling papers themselves looks strong. As more states and countries go legal (Germany, Western Europe’s most populous, is next), the rolling-paper industry is projected to grow by some 70 percent over the next seven years. Even as edibles and vapes cause the smoking slice of the cannabis-consumption pie to shrink, the pie’s overall size is only growing.

But hand-rolled joints? Different story.

All signs indicate that the time-honored, era-defining practice of rolling your own is unlikely to regain its place of prominence in an environment of convenient, impeccable, heavily marketed pre-rolls. Setting his data-analytics role aside and speaking to me strictly as a user, Mitchell Laferla says, “In a lot of ways, as cannabis becomes more mainstream, I see important parts of its subculture becoming diluted. At the same time, more people are getting the experience of smoking a joint than ever before.”

I haven’t driven a stick shift in twelve years, and I can’t remember the last mixtape I made. But I know the last time I rolled a joint. It was three weeks ago. My wife and I had an old friend over for dinner and, after the dishes were cleared, I found my small bag of Afghan Kush, reached for my papers, and rolled something well south of perfect—a little thin, a little bent—but made with love. The three of us passed our slightly sad joint back and forth, the rolling paper slowly disintegrating into pleasure. In a world of beckoning screens and incoming texts, it was one of those rare shared moments.

And as we inhaled, coughed, and laughed, an exchange I had with Levin came back to me: “What about edibles?” I’d asked him, pointedly. “What about tinctures and drinks? You’re selling a single method of ingestion, but now there are dozens of ways to get high. How does that not make you nervous?”

Levin looked at me and his eyes, yeah, they twinkled. “We’re selling a ritual,” he said. “Don’t ever confuse that with an item. Rolling is a ritual; it’s ceremonial. An edible is not going to replace that. You stop doing everything else you’re doing. You sit down, crush it, grind it, roll it, and you’re going to be thinking about that. It’s going to become your focus, your little piece of art.”

This article originally appears in Esquire Magazine.

Need a little more Bluntness in your life? Subscribe for our newsletter to stay in the loop.

11 Signs You've Greened Out and How to Handle It - The Bluntness

Photo by

11 Signs You've Greened Out and How to Handle It - The Bluntness

Photo by  11 Signs You've Greened Out and How to Handle It - The Bluntness

Photo by

11 Signs You've Greened Out and How to Handle It - The Bluntness

Photo by

How to Make a Cannagar Without a Mold: A Comprehensive Guide - The Bluntness

Photo by

How to Make a Cannagar Without a Mold: A Comprehensive Guide - The Bluntness

Photo by

What will you do with that cannabis kief collection? - Make Coffee! The Bluntness

What will you do with that cannabis kief collection? - Make Coffee! The Bluntness DIY: How to Make Kief Coffee - The Bluntness

Photo by

DIY: How to Make Kief Coffee - The Bluntness

Photo by

The Puffco Peak Pro brings style and ease to cannabis dabbing.Image from Puffco on Facebook

The Puffco Peak Pro brings style and ease to cannabis dabbing.Image from Puffco on Facebook The Puffco Peak Pro is easy to hold AND easy to use.Image from Puffco on Facebook

The Puffco Peak Pro is easy to hold AND easy to use.Image from Puffco on Facebook The Puffco Peak Pro allows you to appreciate cannabis and innovation at the same time.Image from Puffco on Facebook

The Puffco Peak Pro allows you to appreciate cannabis and innovation at the same time.Image from Puffco on Facebook

What is reggie weed? - The Bluntness

Photo by

What is reggie weed? - The Bluntness

Photo by